The science

About the Paris Equity Check assessment

Several websites provide equity assessments of the mitigation commitments or policies of major emitting countries. The assessments of www.Paris-equity-check.org has specific characteristics:

Multi-dimensional. Paris-Equity-Check.org reflects the current international debate on equity to drive national emissions trajectories. It does not seek to present a universal vision of equity.

The ‘Equity Map’ shows equitable national contributions according to each of the five categories of effort-sharing quantified in the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report. Each country's Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) - a climate action plan – and their statements on the fairness of their contribution can be compared with each of the five effort-sharing categories.

The ‘Pledged Warming Map’ assumes a differentiated and self-interested attribution of equity approaches to countries, reflecting the bottom-up nature of the Paris Agreement. Each country individually follows the vision of equity (based on capability, responsibility or equality) that is the most favourable.Scientific and peer-reviewed. All the data and methodology contained in this website is peer-reviewed in prestigious scientific journals. The multi-equity allocations of the ‘Equity Map’ is published in Nature Climate Change and the underlying methods are available in an open access journal.

The data and methods of underlying the ‘Pledged Warming Map’ of countries’ climate pledges are published in Nature Communication.Paris Agreement consistent. The national emissions allocations are specifically consistent with the Paris Agreement goals of: net-zero emissions before 2100, peaking of global emissions as soon as possible, and a warming of either 1.5 °C or well below 2 °C. The temperature assessment and national emissions trajectories presented in the ‘Pledged Warming Map’ are based on a bottom-up aggregation of equity that reflects the architecture of the Paris Agreement.

Cost-optimal. The emissions trajectories of all countries add up to cost-optimal global mitigation scenarios selected from the IPCC database, the SSP database or a peer-reviewed study1 that match the Paris Agreement goals.

Comprehensive. The results are available for up to 173 Parties(1) to the UNFCCC.

Long-term assessment. National emissions trajectories stretch until 2100 and provide intermediate emissions targets and net-zero emissions dates.

Multi-gas assessment. Burden sharing is often conveyed through CO2 allocations (called ‘carbon budgets’), while other greenhouse gases (GHG) have a significant impact on global warming. This website presents allocations of GHG emissions (see box below).

(1) The derivation of equitable emissions allocation requires data projection of GDP, business-as-usual emissions. The PRIMAP database does not contain such projections for all countries due to a lack of available data. More details are available in the Methods section of the publication.

Emissions scenarios vs. carbon budgets

Carbon (CO2) budgets are often associated with national and global climate objectives. Due to the long lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere, the temperature at the end of the century depends on the cumulative CO2 emissions rather than on the timing of those CO2 emissions. A linear relationship links the cumulative CO2 emissions to the maximal temperature over the century since the CO2 uptake from the atmosphere by natural sinks (land and ocean) balances almost exactly the global temperature inertia in response to CO2 emissions.

Carbon budgets relate global cumulative emissions over the century to temperature goals. However, using carbon budgets does not provide information on the cost-optimal timing on the mitigation measures to achieve the CO2 mitigation. Carbon budgets also leave out considerations on the other GHG. By contrast, the GHG emissions scenarios from Integrated Assessment Models that budgets are based on are associated with specific policies and technology deployment that minimise the emissions mitigation costs. Using directly using multi-gas emissions scenarios to derive national allocations preserves the information on countries' mitigation measures not just for CO2, but for all the main greenhouse-gases (as defined in the Kyoto-Protocol: methane, nitrous oxide…).

Temperature goals in the Paris Agreement

The choice of a limit to global warming itself represents a choice on equity. Indeed, the climate impacts are unevenly distributed around the globe and affect vulnerable countries the most. A 2 °C warming represents major risks, sometimes existential, for many countries3. As a result, in 2008 a group of 101 countries called for a 1.5 °C warming limit.

In 2013, the UNFCCC initiated a ‘Structured Expert Dialogue’ with over 70 experts to assess the adequacy of the long-term global goal with its ultimate objective. The report on this two-year long review highlighted that:

“The ‘guardrail’ concept, in which up to 2 °C of warming is considered safe, is inadequate and would therefore be better seen as an upper limit, a defence line that needs to be stringently defended, while less warming would be preferable.”

and

“While science on the 1.5 °C warming limit is less robust, efforts should be made to push the defence line as low as possible.”

As a consequence, the Paris Agreement states an aim of:

“Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”

A more detailed analyses of the Paris Agreement temperature goal is available here.

Methodology

NDC assessment

In 1992, under the UNFCCC treaty, countries agreed to pursue mitigation efforts following to their “Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities” (CBDR-RC). With the Paris Agreement, all ratifying Parties must communicate successive Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) that represent a progression in ambition and reflect the “highest possible ambition” with respect to their CBDR-RC. In particular, the Paris Agreement invites developed countries, without naming them4, to take the lead in mitigating economy-wide emissions and in mobilizing climate finance. Historically, few countries have indicated which equity principle5–7 or formula8 they used to derive their mitigation contributions and justify the consistency of these contributions with the principle of CBDR-RC. Instead, many countries simply declared their NDCs to be “fair and ambitious”, either explicitly (e.g. India and the USA9, see national statements on this website) or implicitly by the lack of further explanation.

What is an NDC?

NDCs – Nationally Determined Contributions - are climate action plans that were submitted to the UNFCCC during the lead-up to the Paris Agreement in 2015.

All climate action plans are ‘nationally determined’ and so take many different forms. Most contain a plan to limit the growth of GHG emissions, many also contain adaptation plans, an outline of national circumstances, and a description of the funds needed to carry out their plans.

When countries ratify the Paris Agreement, they have to submit an NDC. The UNFCCC website hosts all of the NDCs submitted so far.

Methodology of the Pledged Warming Map

The Pledged Warming Map provides an assessment of global warming when all countries follow the ambition of a given one. This warming assessment assumes a self-interested approach of equity where each country follows the least stringent of three equity concepts (historical responsibility, capacity to pay and equality). This warming assessment reconciles the bottom-up architecture of the Paris Agreement with its top-down warming threshold.

Why using the Pledged Warming map?

With the Paris Agreement, countries committed to collectively limit global warming to well below 2 °C and pursue efforts to limit warming to 1.5 °C above preindustrial levels. However, there is currently no commonly agreed effort-sharing mechanism to determine the contribution of each country. Measuring the ambition of the climate pledges, the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), requires considerations of effort-sharing driven by equity concepts and countries are requested to provide in their NDC a description of how their contribution is ‘fair and ambitious’ (these are provided under the country graphs).

The international community has long discussed the operationalization of equity following the UNFCCC principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) to drive effort-sharing and derive national emissions allocations. The failure to agree on a top–down mechanism to derive binding national emissions targets for all countries led to a bottom-up situation where countries should pledge NDCs of highest possible ambition.

The first submissions of these bottom-up NDCs do not add up to a global ambition consistent with the joint temperature goals. A five-year stocktake, starting in 2020, requires all countries to pledge enhanced actions and support. The absence of agreement on a unanimous operationalization of the CBDR-RC should not be used as an excuse for inaction and should not leave the international community without a metric reflective of current agreements to assess the ratcheting-up process.

How to use these results of the Pledged Warming Map?

Taking stock of NDCs and ratcheting-up ambition

The warming metric used in this website relies on a combination of equity concept where each country follows the least-stringent equity approach (from capability, historical responsibility or equality). This hybrid combination reflects the bottom-up pledge-and-review architecture of the Paris Agreement provides a warming assessment of countries’ NDCs. The results can inform the ratchetting-up process on the ambition of current emissions targets without hypothesizing an international agreement on a single approach of equity. The emissions trajectories can be used by experts and decision makers to derive emissions targets in line with the Paris Agreement mitigation goals.

Climate litigation cases

This hybrid combination of countries’ least-stringent equity approaches is also relevant to climate cases where the court only rules for the least-ambitious end of an equity-based range.

The multiplicity of equity concepts results in a wide range of emissions allocations for countries and regions that is sometimes used as an uncertainty range by non-experts. In a recent climate case, the District Court of The Hague ruled that the Dutch government has to reduce 2020 emissions to at least the least-ambitious end of the range recommended by the IPCC-AR4 for the Annex I country group based on multiple equity allocations from 16 studies. The court did not pick an approach of equity and ruled for the minimum effort consistent with international treaties in light of commonly reviewed science. While the multiplication of climate litigations cases against governments can contribute to the ratcheting-up process, systematic court decisions that governments must follow the least-ambitious end of an equity range would be insufficient to achieve the Paris Agreement. The trajectories presented here follow the least-stringent equity concept for each country individually but are collectively consistent with the Paris Agreement warming thresholds. Using the trajectories presented here to derive emissions target and phase-out dates enables to conform with the ambition of the Paris Agreement without selecting and applying a universal concept for all countries.

More information in the underlying peer-reviewed study.

The data of the Pledged Warming Map is available here. Please inform the author Yann Robiou du Pont of its use and cite as indicated in the Credits section.

Methodology of the Equity Map

Global cost-optimal emissions scenarios

Unlike most earlier studies, the method used here ensures that emissions are allocated to countries such that the global aggregate of these national allocations is compatible with the global cost-optimal emissions scenario.

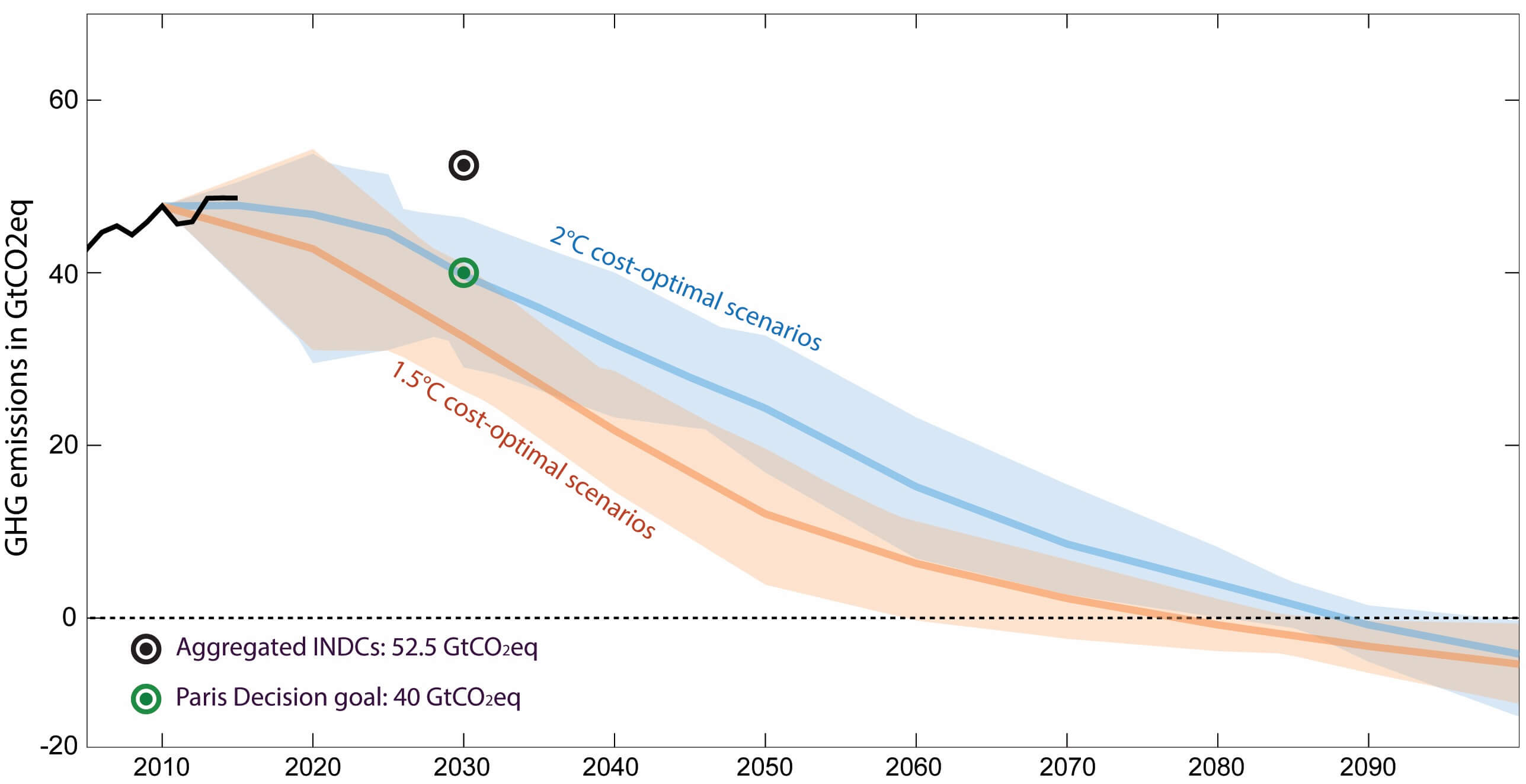

The global cost-optimal emissions scenarios used here were specifically selected to match the goals of the Paris Agreement, namely: net-zero emissions before 2100, peaking of global emissions as soon as possible, and maximum warming of either 1.5 °C or well below 2 °C.

The selected global emissions scenarios (from the IPCC database and a peer-reviewed study1), include land-use and international aviation and shipping emissions, and have the following features:

global emissions peaking by 2020,

global net-zero emission by 2100,

at least a likely (>66%) chance of limiting global warming to below 2 °C for the rest the century,

a subset of 1.5 °C scenarios with a more likely than not (>50%) chance of returning to below 1.5 °C of warming in 2100.

In 2030, the average emissions level of the selected 2 °C scenarios is 39.7 GtCO2eq, which is almost equal to the indicative goal of 40 GtCO2eq of the Paris Decision, and the 1.5 °C scenarios have average 2030 emissions of 32.6 GtCO2eq. Following 2 °C scenarios results in net-zero emissions as early as 2080, while 1.5 °C scenarios become negative between 2059 and 2087.

The maximum annual mitigation rates of the 2 °C scenarios over the 21st century is 2.1%/y in 2025 (and 1.6%/y on average over the 2030-2050 period). The annual mitigation rate of the 1.5 °C scenarios reaches 2.3%/y in 2039 (and 2.2%/y on average over the period 2030-2050).

Range and average of global cost-optimal emissions scenarios, including land-use and bunker emissions, consistent with the Paris Agreement goals.

Equity Allocations

National emissions allocations are quantified following the five equity categories presented in the IPCC-AR5 WGIII Ch. 6 (figure 6.28). The methodology is detailed in this study, and the formula and parameterization available here. Each of these allocation approaches allocates the emissions of the cost-optimal scenarios presented in the “Temperature goal” section, but exclude emissions from the land-use sector and from international aviation and shipping. The national equitable emissions allocations presented in this website can be met with a combination of domestic mitigation, internationally traded emissions mitigation11 and support towards global mitigation.

|

Allocation name |

Code |

Allocation characteristics |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Capability |

CAP |

Capability |

Countries with high GDP per capita have low emissions allocations. |

|

|

Equal cumulative per capita |

CPC |

Equal cumulative per capita |

Populations with high historical emissions have low emissions allocations.

|

|

|

Greenhouse Development Rights |

GDR |

Responsibility-capability-need |

Countries with high GDP per capita and high historical emissions per capita have low emissions allocation.

|

|

|

Equal per capita |

EPC |

Equality |

Convergence towards equal annual emissions per person in 2040. |

|

|

Constant emissions ratio |

CER |

Staged approaches |

Maintains current emissions ratios, preserves status quo. |

The data of the Equity Map is available here. Please inform the author Yann Robiou du Pont of its use and cite as indicated in the Credits section.

References

-

Rogelj, J. et al. Energy system transformations for limiting end-of-century warming to below 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 519–527 (2015).

-

IPCC. in Climate Change 2014, Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (ed. Edenhofer O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Z. and J. C. M.) 1–33 (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

-

Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Differential climate impacts for policy-relevant limits to global warming: the case of 1.5 °C and 2 °C. Earth Syst. Dyn. Discuss. 6, 2447–2505 (2016).

-

Voigt, C. & Ferreira, F. Differentiation in the Paris Agreement. Clim. Law 6, 58–74 (2016).

-

Commission of the European Communities. Impact Assessment: Document accompanying the Package of Implementation measures for the EU’s objectives on climate change and renewable energy for 2020 Proposals. (2008).

-

Japan. Submission by Japan - Information, views and proposals on matters related to the work of Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) Workstream 1. (2014).

-

Nepal on Behalf of the Least Developed Countries Group. Submission by the Nepal on behalf of the Least Developed Countries Group : Views and proposals on the work of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action ( ADP ). (2014).

-

BASIC experts. Equitable access to sustainable development: Contribution to the body of scientific knowledge. BASIC expert group: Beijing, Brasilia, Cape Town and Mumbai (2011).

-

UNFCCC. Submitted NDCs. (2016). Available at: http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/indc/. (Accessed: 5th February 2016)

-

Meinshausen, M. Climate College - NDC Factsheets. (2015). Available at: http://climatecollege.unimelb.edu.au/indc-factsheets/.

-

UNFCCC. Paris Agreement. (2015).

-

Baer, P., Fieldman, G., Athanasiou, T. & Kartha, S. Greenhouse Development Rights: towards an equitable framework for global climate policy. Cambridge Rev. Int. Aff. 21, 649–669 (2008).

-

Kemp-Benedict, E. Calculations for the Greenhouse Development Rights Calculator. (2010).

-

Meinshausen, M. et al. National post-2020 greenhouse gas targets and diversity-aware leadership. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1–10 (2015). doi:10.1038/nclimate2826

-

Caney, S. Justice and the distribution of greenhouse gas emissions. J. Glob. Ethics 5, 125–146 (2009).